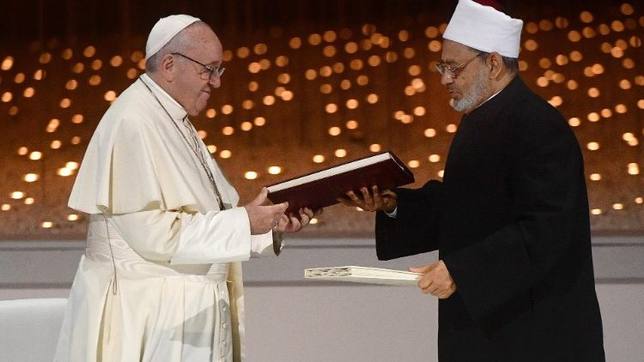

The First International Day of Human Fraternity takes place on February 4, 2021, and Pope Francis will participate in a virtual meeting with the Grand Imam of Al-Azhar, the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Mr. António Guterres, and other personalities.

*****

By Fr. Jesús Villagrasa, LC

Editorial of Ecclesia magazine XXV, no. 1, 2021 – pp. 3-10

Expressions such as “human family” or “universal fraternity” seem to be analogies or images, so forced that their use appears to be an abuse, or at least an appeal to the vague subject of an unrealizable process of harmonization of the multiple and complex dynamics linked to globalization.

Neither one nor the other. The expression “human family” means the human race and connotes the factual or moral unity of this race, the equality of all men, and an indelible human aspiration for fraternity and peace. The expression is not alien to common language, but neither its content is so clear, nor should its practical recognition in everyday life, international relations, and local affairs be taken for granted.

In public life, “human family” is an often forgotten category; it is recurrently found almost exclusively in the Magisterium of the Catholic Church, where it holds an important place. Pope Francis’s latest encyclical bears a title from a phrase of St. Francis with a similar meaning: Fratelli tutti, brothers all. The Second Vatican Council states in the constitution Lumen gentium (LG) that the Church has received from God the high mission of being “a sign and instrument of the intimate union with God and of the unity of the whole human race” (LG, 1). This mission became a priority for John Paul II who, addressing the Roman Curia on the occasion of the presentation of Christmas greetings (December 21, 2004), said: “Dear brothers, let us each day become more aware that union with God and the unity of the whole human race, starting with believers, is our primary commitment” (no. 4). The unity of the Church and the unity of the human race are a deep aspiration of Christians and beat in the hearts of men: “I often perceive – he concluded in the same speech – this longing for unity in the faces of pilgrims of all ages” (no. 6).

The idea of a “human family” is already present in the earliest books of the Bible and in ancient Greek and Roman thought; it was deepened and enriched by Christianity, and appears in the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of the UN (1948) and in the Second Vatican Council.

The first chapters of the Bible show that all humanity descends from the first parents, Adam and Eve. Adam’s “solitude” and the basic forms of relationship – the ‘alterity’ of Adam-Eve and Cain-Abel, and the ‘we’ of the human family – are already present in the Genesis account. Sin breaks the unity of the human race and spreads in increasingly penetrating forms (cf. Gn 3-9).

Throughout history, God seeks to save humanity and gather it through various stages. “The covenant with Noah after the flood (cf. Gn 9:9) expresses the principle of divine economy with the ‘nations,’ that is, with men grouped according to their countries, each according to their language, and according to their clans (Gn 10:5)” (Catechism of the Catholic Church – CCC – 56).

The “table of nations,” in Genesis 10, expresses the realization of a divine blessing upon humanity, viewed as a single family composed of different members. At the beginning of salvation history, precisely when humanity emerges from the flood, this text almost programmatically emphasizes the unity of humanity and, at the same time, the positive value of diversity. If the “table of nations” shows the positive value of unity in the diversity of peoples, the dispersion resulting from the Babel tower project, in Genesis 11, shows by contrast the negative value of division. A project of unification of peoples can turn into “dominion,” and diversity can generate “confusion.” In God’s divine plan of salvation, this order of the plurality of nations “is destined to limit the pride of a fallen humanity that, united in its perversity (cf. Sb 10:5), would like to make its own unity in the manner of Babel (cf. Gn 11:4-6)” (CCC 57).

The contrasting visions of unity and diversity presented in Genesis 10 and 11 will find their synthesis in the passage of Abraham’s migration (Gn 12:1-3), which constitutes the conclusion of the origin story and the beginning of the patriarchal history. Abraham’s migration, the “name” (v. 2), and the blessing for all the families of the earth oppose the migration of the builders of Babel’s tower (11:2), the “name” they seek to make for themselves (11:4), and the dispersion that closes the episode of the tower. To gather all dispersed humanity, to reconstitute the human family, God chooses Abram and calls him to leave what was most his own and dear—his country, his kin, the house of his father—to make him Abraham, that is, “the father of a multitude of nations” (Gn 17:5): “By you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Gn 12:3).

“The people born of Abraham will be the custodians of the promise made to the patriarchs, the chosen people (cf. Rm 11:28), called to prepare the gathering one day of all the children of God in unity of the Church (cf. Jn 11:52; 10:16)” (CCC 60). In the descendants promised by God to Abraham, all the peoples of the earth will be blessed. This descendants will be Christ (cf. Ga 3:16), in whom the outpouring of the Holy Spirit will form ‘the unity of the children of God scattered’ (cf. Jn 11:52)” (CCC 706).

The idea of a “human family” is found, in an embryonic form, in the ancient Greco-Roman world from the earliest testimonies; in Homeric poems, even in the proper sense as kinship by blood, due to the genealogical stories from which classical religion and primitive pre-philosophical thought draw: gods and men are seen as related and “children” of divinity. Zeus is the “father of men and gods.” Archaic Greek has a strong sense of the unity of the human race. However, later historical development, especially during the Persian Wars, tends to emphasize motives of differentiation between Greeks and barbarians.

The flourishing of sophistic, philosophical, and scientific thought in the 5th century BC, although sometimes seeming to provide theoretical-scientific support for “racist” theories, generally constitutes a moment of profound reflection on man that will eventually conclude, thanks also to political events such as the empire conquered by Alexander the Great and the Roman Empire, in a universalism as the first present in Hellenistic philosophies and later in the thought of Cicero and Seneca.

These and other nascent thoughts in Greek philosophy will develop thanks to Christianity. Consider, for example, concepts such as person and community. The great ancient philosophers had already pointed out the greatness of the person: the spiritual dignity of their intellectual life, their deep aspiration to the absolute, the moral life of their conscience, their capacity to seek what is true, good, and beautiful. They also showed the close relationship between person and community. It suffices to mention Plato’s considerations on the origin of community: it arises from multiple human needs (Plato, Republic 369 b). Aristotle believed that man is a social animal and, even if he had no needs to satisfy, he desires to live in community (Politics III, 6, 1278 b), for, by nature, the person desires communal life for itself and not only for its utility. Living in community is natural to man. These visions of the naturalness of communal life were burdened by some structural limits, as there was a lack of clear and strong transcendence of the person over the political community.

Christianity enriches the idea of the “human family” and purifies and brings to fullness the concepts of person and community. The unity of the human race is one of the most beautiful and, at the same time, most demanding messages that Christianity, as leaven of history and civilization, has introduced into culture. And this because the idea of person, seen in its eminent dignity, is the fruit of biblical inspiration – especially New Testament – and because, from a conceptual point of view, it was formed within the trinitarian disputes during the great ecumenical councils of antiquity, and later enriched by the thought of the Church Fathers, and of medieval and subsequent philosophers and theologians. Parallel to the history of the concept of person, the concept of community develops thanks to Christianity.

From the experience of faith in Jesus Christ, dead and risen, the first Christian communities overcame not only the limits of ancient philosophical conceptions but also the ethnocentrism of the Jewish tradition and opened themselves to welcoming foreigners. Jesus expands the biblical commandment of love of neighbor to embrace the stranger and the enemy. He welcomes everyone as brothers: the poor, the sick, sinners, women, and children, excluded from their society. In Jesus Christ, united with the human condition and redemptive through his death on the cross, the first Christians recognize the Son whom God exalted, making him Lord of all.

This faith in Christ the Lord underpins the Christian mission open to all peoples, without distinction of near and far, Jews and pagans, belonging to their own ethnicity or foreigners. Paul of Tarsus has a specific vocation to broaden the horizons of the preaching of the Christian faith. Following in his footsteps, the disciples of Jesus Christ, with the strength of the Spirit, traverse a “borderless” world, proclaiming a God who is Father of all, who welcomes and forgives everyone, even to the ends of the earth. The divine mission surpasses all ethnic, religious, and cultural barriers to form from different and divided peoples a single humanity, new and reconciled; and every time these barriers are reconstituted, Christians should find in their faith the strength to tear them down.

Christianity has contributed to awakening in men a stronger and more vibrant consciousness of the dignity of each person and of the natural unity of the human race. This general conviction is reflected in the use of “human family” in the preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, which seems to suggest an ontological fact: that all men, in one way or another, derive from a single principle and, therefore, have the same nature and equal dignity. This fact is a basic premise of the entire declaration. In fact, the preamble begins with this statement: “Freedom, justice, and peace in the world are based on the recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family.”

This declaration is the first clear internationalization of human rights, as previously they were considered an internal matter of States. In fact, the only action of a government outside its borders was diplomatic protection exercised in favor of its own citizen, but not as a dignified person and subject of rights valid everywhere, but as a protected subject. After the crimes of World War II, the international community grew convinced that above the sovereignty of States lies respect for the dignity and rights of man, as man, because he is man and a member, precisely, of the human family.

The Second Vatican Council uses the term “human family” at least forty times. It is another way of signifying the unity of the human race, but with a particular connotation. The expression lends itself, without a doubt, as a rhetorical device for moral exhortation. But, beyond exhortation, “human family” primarily refers to an ontological fact, to a “being,” and only as a consequence to a “must be”: a task, a moral challenge, and a goal for its members. In fact, the Council articulates these three meanings or dimensions of the “human family”: ontological fact, ethical task, and goal.

In the texts of Vatican II, the idea of the “human family” appears as an evident fact of the human condition: it is often spoken of as if it were indisputable that all men biologically and ontologically form a unity (GS, 2, 3, 29, 37, 38, 56, 57, 63, 74, 86, DH, 15, IM, 3). This ontological fact, in recent decades, seemed better perceived. “History itself is subjected to such a process of acceleration that man can hardly follow it. The human race runs the same course and no longer diversifies into several dispersed histories” (GS, 5). With its ingenuity, through science and technology, and “especially with the help of the increased means of exchange among nations, the human family is feeling and becoming a single community in the world” (GS, 33). The Council Fathers express joy in seeing that humanity, after the immense wounds of the world wars, is regrouping, in fact, into a new and close “civil, economic, and social unity” (LG, 28).

From observing the growing interdependence among nations, the Council derives an idea of the common good increasingly universal, which involves “rights and obligations that concern all of humanity” (GS, 26). In fact, the Council notes that the human family has reached a crucial point in its development where only the achievement of universal peace can save it (cf. GS, 77). On the one hand, therefore, Vatican II observes with satisfaction that the unity of the human family is being achieved; on the other hand, its dramatic aspect is not silenced, for in the atomic age, the potential for conflicts has reached such a dimension that only their peaceful regulation at a planetary level can save humanity from catastrophe. In the Council, the idea of the human family is present both in the context of the nature of things and in the contemporary situation, as well as in the ethical consciousness.

The idea of the “human family” in Vatican II also exists in a tension between two poles: creation and the eschaton. It is already a family, but not yet fully. The fact of coming from a single Creator makes us brothers by nature, but we must become a family and a family of God; this is the ultimate goal toward which God leads men: we are brothers by vocation and grace: “God the Father is the beginning and the end of all. Therefore, we are all called to be brothers” (GS, 92). Between creation and the eschaton lies the history of sin and salvation. Therefore, the realization of the unity of men must pass through a work of redemption and regeneration. The unity of the human race is not a peaceful starting point, untouched by subsequent situations, nor is there an evolutionary process that inexorably leads humanity toward that goal. The human family is a unity of origin and destiny; the first is a fact; the second, however, must be conquered and built. The idea of the human family as the family of the children of God does not oppose the unity of the human race rooted in its natural origin and striving for unity in its current scientific, economic, social, and political development: its unity, understood as a gift of grace and fruit of Christ’s salvific work, opposes only the “power of darkness,” that is, the power of sin that distorts the divine plan of creation (cf. GS, 37).

The mission of the Church, which proposes itself as a sacrament of the union of men with God and of the unity of the human race, is part of this salvific work of Christ:

To be the sacrament of the intimate union of men with God is the primary purpose of the Church. As the communion of men resides in union with God, the Church is also the sacrament of the unity of the human race. This unity has already begun in her because she gathers men “from every nation, race, people, and language” (Rev 7:9); at the same time, the Church is “a sign and instrument” of the full realization of this unity that is still to come (CCC 775).

From its origin, the Church is universal, Catholic. John Paul II affirmed before the Diplomatic Corps accredited to the Holy See, on January 10, 2005, that for the Christian, every man is a brother: “The Catholic Church, universal by nature, is always directly involved and participates in the great causes for which the modern man suffers and hopes. She does not feel foreign among any people, because wherever a Christian, her member, is present, the whole body of the Church is present. Moreover, wherever a man is found, a bond of fraternity is established for us there” (no. 3).

In the encyclical Fratelli tutti, the idea of the human family develops under the form of universal fraternity; it is “an open fraternity, which allows recognizing, valuing, and loving each person beyond physical proximity, beyond the place in the universe where they were born or dwell” (no. 1). To recognize it requires a “heart without borders, capable of going beyond the distances of origin, nationality, color, or religion” (no. 3).

In the final appeal, Pope Francis recalls the theological premise: that God “created all human beings equal in rights, duties, and dignity, and called them to live as brothers among themselves” (no. 285). The Pope invites us to dream, pray, and commit ourselves